This problem remains widespread. Many employers — at a guess the great majority — still think that if a man says he’s a woman, it’s against the law to refuse to let him use the women’s toilets, changing rooms etc.

They’re wrong. If a man says he’s a woman, he has the protected characteristic of gender reassignment, and he’s entitled not to suffer discrimination or harassment because of that. But if he’s told he’s not allowed to use women’s facilities, that’s not because of his gender reassignment: it’s because of his sex. If employers are allowed to provide single-sex facilities at all (and I’m not aware of anyone ever having suggested they’re not), they’re allowed to exclude all men from them, including any men who say they are women. There is no plausible basis on which such a man could argue that he had suffered unlawful discrimination by being excluded from women-only facilities.

But if you’re a woman and you find a man using supposedly female-only facilities at work, it doesn’t help you hugely to know that your employer is wrong in its belief that it has to let him do so. What can you do?

Your legal rights

As an employee, you have a right not to suffer indirect discrimination because of your sex, or harassment related to your sex. In letting a man (or men) use the women’s facilities in your workplace, your employer is almost certainly subjecting you to both of those kinds of legal wrong.

How can you persuade your employer to respect your rights?

This should be what your union is for, but I can hear your hollow laugh from here. Maybe somewhere out there there is a trade union that thinks women’s rights to everyday privacy and dignity (not to mention safety) are as important as the preference of men who think they are women not to be faced with the reality that there are other people who don’t agree, and is vigorously defending its female members rights. I have yet to hear of this happening.

Many women who reject gender identity theory have either left their unions in disgust at their attitudes to women’s rights, or decided not to bother joining one. Some have joined the Free Speech Union instead, which has helped a number of employees with cases of this nature already (David Toschak’s case is the most recent example), and is definitely worth considering.

All the same: if you are a member of a trade union, this is what it is for. So I’m inclined to say you should proceed on the assumption that it will do its job properly, and approach local officials for help. You may get lucky.

If you’re not a member of a union or the FSU, or your union won’t help, you’ll be on your own with your employer’s grievance process and ultimately, if you feel strongly enough, a complaint to an employment tribunal. If you can get a group of colleagues together to present grievance together, so much the better.

Think about your risk appetite

Before you take any of those steps, think hard about what you’re prepared (and can afford) to risk. Being known to dissent from gender identity theory (or to be “gender critical”) is enough in itself to attract the attention of bullies in many workplaces. Taking positive steps to assert your right to female-only spaces at work may make you unpopular with colleagues and/or managers, and if you object even in the politest possible terms to your employer’s policies, you may be marked out as a trouble-maker. Even if your initial plan is to raise a grievance but take matters no further if the grievance fails, things can escalate. If you end up being bullied because of your grievance, or because you’ve “outed” yourself as “gender-critical”, you may find yourself locked into a dispute with your employer in which you are effectively forced into litigation as the only effective way of defending yourself.

Litigation itself is always a pretty nuclear option. It won’t endear you to your employer, and it may well damage your prospects of promotion, or passing your probationary period, or a renewal of your fixed-term contract, or surviving the next redundancy exercise. Punishing you in those kinds of ways for enforcing your rights in the employment tribunal is also a legal wrong, of course, but proving that that is what has happened to you is unlikely to be straightforward. Like most employment lawyers, I routinely remind my clients that for most people, most of the time, a job is a better thing to have than even the most cast-iron employment tribunal claim; and few employment tribunal claims are cast-iron.

I hate saying this, because what it boils down to is that sometimes, for self-preservation, people have to let bullies win. But if losing your job would spell financial disaster for you, you may have little real choice but to leave these battles for others to fight.

Raise a grievance

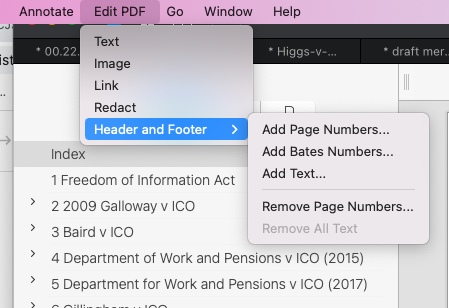

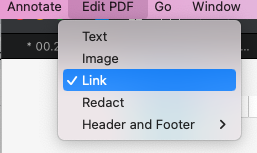

If you’ve thought through the risks and you’re prepared to take them, read your employer’s grievance process and follow it. Document everything. If you have a meeting or a call with someone, drop them a polite email straight after setting out your understanding of what passed between you. Take notes during calls or meetings and file them away. Sex Matters has good advice and helpful precedents and factsheets here.

However furious you feel, keep all your communications calm and as concise as possible. Never, ever hit send on an email while your pulse rate is still raised.

I’m going to labour this point, because the combination of sanctimoniousness and gas-lighting with which women who raise these matters are often met is infuriating, so unless you’re an actual saint, you are likely to get very cross. At the same time, losing your temper may give your employer or your bullies the excuse to mistreat you that they most want. So try to make a game of combining persistence with a reasonable, unruffleable manner. It’s easier to stay calm in the face of provocation if you’ve seen the provocation coming and planned for it.

But also, hold your nerve. The time to decide the level of your risk appetite is before you take the first step. If you have decided to tackle this with your employer, do so calmly and politely, but not half-heartedly or apologetically. Bullies feed on fear, so even if you’re quaking inside, try not to let it show. There is nothing even arguably unreasonable about standing on your right not to find men in women-only spaces.

In particular, make a decision in advance about what you will do if you actually encounter a man in supposedly women-only facilities. It seems to me there are three options:

- Challenge him.

- Leave.

- Pretend not to notice.

Each of these options has its risks and drawbacks. If you decide to challenge the intruder, do so politely and calmly. Don’t be drawn into an argument, and don’t elaborate on the reasons why you object to his presence: just tell him that you don’t think he should be using the women’s facilities, because he’s not a woman. Even so, he may well complain that you have harassed him, so be ready for that. Write down your own account of the encounter as soon as you can.

Even if you just leave on finding a male intruder in a women-only space, there’s a risk that he will complain that by doing so, you have made it obvious that you don’t see him as a woman, and thereby harassed him. So if this is your choice, leave without any outward display of irritation or affront; and again, make a note of the encounter as soon as you can.

In either case, if you are accused of harassing a male colleague for objecting to his presence in supposedly women-only facilities, that will be various kinds of legal wrong, but most obviously discrimination because of your protected sex realist/gender-critical belief. The main point of keeping your cool is to deprive your employer of what I’ve taken to calling the Bananarama defence: “It’s not what you said, it’s the way that you said it.”

Pretending not to notice is the safest option from the point of view of accusations of harassment, but it has the down-side that if you end up in an employment tribunal, it may be said that the fact that you continued to use the facilities meant you didn’t really mind. So make notes of any encounter, including how it made you feel and why you decided to keep your head down.

Complain to an employment tribunal

If your grievance doesn’t have the result that your male colleagues are told to stop using the women’s facilities, the obvious next step is an employment tribunal claim. There are strict time limits for these. Before you’re allowed to bring an employment tribunal claim, you have to go through a process called “early conciliation” with ACAS), and you must start that by notifying ACAS of your complaint within 3 months less one day of the act complained of. If you’re complaining about a policy that is still in place and still having consequences for you, this is unlikely to give you any difficulty; but if for any reason it stops having practical consequences for you, make sure you notify ACAS within 3 months of the last time it did. ACAS will send you a certificate once early conciliation is finished, and then you can present your claim to the employment.

How can I afford to litigate?

Legal fees mount up fast. Unless you’re on the kind of income that means you can buy a flash sports car without breaking sweat, you can’t afford to instruct lawyers to act for you in an employment tribunal claim out of your own resources. I can think of the following options, some of which you can try at different times in the same case, or in combination with each other:

- Trade union assistance: if you’re lucky enough to be a member of a trade union that takes its female members’ rights seriously, they may provide you with legal advice and representation.

- If you’re a member of the Free Speech Union, they may back your case.

- You may have legal expenses insurance tucked away in your household insurance policy, or your car insurance, or insurance attached to a credit card, etc, so read the small print of all these things.

- Apply to the JK Rowling Women’s Fund. This is a wonderfully generous and practical initiative, but it’s inundated with requests. So do apply, but don’t assume you’ll get help from it in time to start a claim, and don’t miss deadlines while you are waiting to hear.

- Run the case yourself. You don’t have to pay a fee to bring a claim in the employment tribunal, and tribunals are supposed to be informal and accessible to non-lawyers. The truth is, they’re pretty daunting for non-lawyers, so if this turns out to be your only option for enforcing your rights, do think hard about whether you can cope with the work and the stress. If you’re thinking seriously about this option, I’d suggest getting hold of a copy of ET Claims: tactics and precedents: the 4th edition was published in 2013, so it’s getting a bit long in the tooth now, but it’s mostly not the kind of material that goes out of date very fast. (Authors’ royalties go to the excellent Free Representation Unit.)