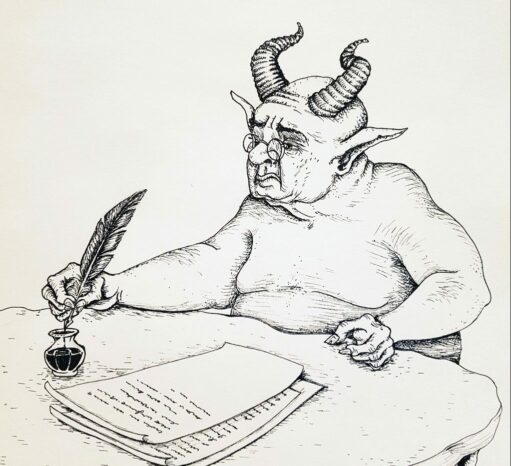

In civilised life domestic hatred usually expresses itself by saying things which would appear quite harmless on paper (the words are not offensive) but in such a voice, or at such a moment, that they are not far short of a blow in the face… You know the kind of thing: “I simply ask her what time dinner will be and she flies into a temper.” Once this habit is well established you have the delightful situation of a human saying things with the express purpose of offending and yet having a grievance when offence is taken.

CS Lewis, The Screwtape Letters (in which an experienced Devil coaches his nephew in the art and science of temptation)

The other day, Acas tweeted out the suggestion that putting pronouns in email signatures could help create a more open and inclusive workplace. Legal Feminist disagreed:

There followed a storm of engagement, unprecedented for the Legal Feminst account: over 600k impressions, over 500 quote tweets and nearly as many retweets. I think the quote tweets in particular are revealing, and they are the main subject of this blog.

But before I get to that, I want to explain the context a bit; this will be old hat for many of my readers.

The gender war: a quick primer

There are two sides in this war. They call each other various names, but we can call them sex deniers and gender criticals.

Sex denialism claims that sex doesn’t matter. Whether you’re a man or a woman depends not on your body, but on your inner sense of identity. A male person who says that he is a woman should be treated, referred to – and even thought of – as a woman for all purposes; and vice versa. Various things follow. If a man wants to join a support group for female survivors of male sexual violence, then provided only he says he’s a woman, he must be welcomed in. If a man with fully intact male genitalia wants to undress in the women’s changing area at the swimming pool, anyone who objects is a pearl-clutching prude and a bigot. If a mediocre male athlete wants to compete in women’s events and start breaking records and winning medals, the women should move over. If a male doctor wants to identify as a woman, his true sex is none of his patients’ business – even where intimate examinations are concerned. If a rapist decides he’s a woman and wants to be moved to a women’s prison, that’s his right too.

Gender criticals think biological sex does sometimes matter: for healthcare, for safeguarding, for everyday privacy and dignity, for fairness in sport, and so on. They think sex is determined by whether you have a male or a female body, and that it’s no more possible literally to change sex than to change species.

The attentive reader will have noticed that the “gender critical” viewpoint is made up of commonsense propositions that until about ten minutes ago no sensible person – whether on the political left or right – would have dreamed of contesting. The sex denialist beliefs are novel, and surprising.

Pronouns

So where do pronouns come in?

This takes us to the manner in which sex denialism has been promoted. You can’t defend irrational beliefs with reason. By and large sex deniers don’t try: instead, their strategy has been to attempt to leapfrog over the usual campaigning, lobbying, arguing, persuading phases of bringing about profound cultural and legal change, and to pretend instead that the desired outcome is already accepted by all right-thinking people – and to silence dissent by visiting dire consequences on anyone who questions that claim. That, I believe, is the whole reason for the vitriol and toxicity that surrounds this subject. Anyone who points out the absurdity of propositions like “some women have penises” must be howled down as a bigot, shamed, no-platformed, hounded from her job, kicked off her course, etc. That way, any doubter who lacks an appetite for martyrdom will be persuaded to steer clear of the whole debate – and insist if pressed that this subject is all too complicated and toxic, and they simply haven’t found the time or head-space to form a view.

The more insidious part of the strategy is the first part: the pretence that the contentious propositions that form sex denialism are already accepted without question by all educated, right-thinking people. Sex deniers make determined efforts to weave their claims seamlessly into our language and the fabric of our workplace culture, with the aim of converting contentious claims into the kind of tacit knowledge that doesn’t even need to be stated or formulated.

Acas’s advice

So what does Acas mean when it says announcing your pronouns can help create a more “open and inclusive” workplace? Inclusive for whom, and how? Your colleagues and work contacts will mostly know whether you’re male or female, if they need to. If you have an androgynous name and you particularly want to announce your sex, adding a title after your name will clear up any ambiguity with much less accompanying baggage than pronouns. But why do we even need to do this? Those who reply to my emails don’t need to know whether I am female or male. The truth behind pronouns is that their “baggage” is the point. The mechanism by which pronouns are supposed to make the workplace more open and inclusive is that they demonstrate your support of sex denialism, but without requiring you to say anything explicit. They bolster and entrench the idea that gender identity is more important than sex, while maintaining the appearance of a trivial, harmless courtesy.

That’s why I think our tweet was right. The claims of sex denialism are far from universal: on the contrary, they are bitterly contentious. By putting pronouns in your signature you raise a flag that aligns you publicly with one side – and against the other – of the gender war. If you’re a Catholic pupil at a school in Glasgow where “No Pope!” is the standard greeting (I am not making this up – I have it on reliable authority that it’s an example drawn straight from life), you’re put to an invidious choice: either play along – or out yourself as a Catholic or Catholic-sympathiser. No doubt the greeting makes the environment feel welcoming and inclusive for the children of Rangers supporters; less so for young Celtic fans.

Given the bitterness of the dispute – and especially given the many occasions on which gender critical individuals have had their jobs, their livelihoods or even their physical safety threatened – being put to the parallel choice by pronoun rituals is not going to make the workplace feel open and inclusive for gender-critical employees.

An accidental behavioural experiment

Are you feeling sceptical? Thinking maybe I’m overreacting, over-interpreting a harmless bit of politeness? I sympathise. When I first came to these debates, that’s what I thought, too. Why’s everyone getting so het up about language? Can’t we just be polite – can’t we use the words preferred by people who care passionately about words, and focus on what matters?

If that’s where you are – re-read the short extract from The Screwtape Letters at the top of this blog, and consider the manner in which the original tweet has operated as an accidental behavioural experiment.

On the face of it, it’s quite a dryly techie tweet from a legal account, disagreeing with a bit of HR advice from Acas. But it’s had an extraordinary level of engagement: at the time of writing, nearly 700k impressions, hundreds of retweets and quote tweets, and nearly 3,000 likes.

So what’s going on? Why has it attracted so much attention?

I think the clue is in the quote tweets. They’re almost all hostile, and Twitter is a rage engine. Most fall into one of two categories: either words to the effect “What’s your problem with this trivial courtesy? Get a life!” or else “Ha ha nasty TERF bigots deserve to feel excluded and fearful.” I’ve done a rough-and-ready analysis, sorting about the hundred or so of these quote tweets into categories. I counted 66 that fell into the “ha ha nasty terven” category, 26 into the “harmless courtesy” camp – plus two that agreed with the original tweet and a few I couldn’t easily classify.

The typical HR response to any push-back against pronoun rituals is of the “harmless courtesy” flavour. Why, they ask, are you making such a big deal of this little thing? Why can’t you just be kind and polite like everyone else? Or at least not make an ungracious fuss if your colleagues want to be kind and polite! If you argue that pronoun rituals are an attempt to make a particular highly contentious belief system seem so mainstream that it can be treated as the default – and shame anyone who doesn’t subscribe to it – you’ll be met with polite bafflement. “What makes you think it’s that? It’s just a trivial courtesy that will make a marginalised group feel a little bit more comfortable. How much can it possibly cost you?”

This type of response was well represented in the sample I looked at. Here’s a typical one:

This is a perfectly understandable take from decent, well-intentioned people who haven’t given the matter a great deal of thought. But it’s hard to sustain in the teeth of the evidence provided by the other, much larger category of quote tweet. There are more than twice as many of these as from team “harmless courtesy”, and they make my case for me vividly – sometimes in unmistakably menacing terms. Here’s a small sample of that type:

This was a reply, not a quote tweet

The first of these is admirably clear: “MAKE THE BIGOTS STFU [for the pure in heart, that translates “shut the fuck up”]. THAT’S THE BLOODY POINT.”

This is the heart of the matter. A handful of responses of this type might have been explained away as the bad behaviour of a few hotheads. But the numbers involved make that impossible to sustain.

A clear majority of the hundreds who have engaged with this tweet by quote-tweeting it are saying in terms that the point of including pronouns in email signatures is to make “TERFs” feel excluded and fearful.

The quote tweets have vividly dramatised both aspects of the technique recommended by Uncle Screwtape in the extract at the start of this blog: one group (Zoë Irene et al) boasting that they are indeed saying something with the express purpose of giving offence – while the other group takes on the role of maintaining a sense of grievance when offence is taken.

Expressing loathing and contempt for those who hold gender-critical views may be fashionable; it even seemed to have a degree of judicial sanction until the first instance decision in Forstater was corrected on appeal. But the lesson from the judgment of the Employment Appeal Tribunal in Forstater needs to sink in. Gender-critical beliefs are within the protected characteristic of “religion or belief” (so too, probably, is sex denialism); harassing or discriminating against your employees on grounds of their protected beliefs can prove expensive. One of the things to be taken into account by a court or tribunal in determining for the purposes of a claim under the Equality Act whether conduct has the purpose or effect of violating the victim’s dignity or creating an intimidating, hostile, degrading, humiliating or offensive environment for them is whether it’s reasonable for it to have that effect. The fate of this tweet could itself provide telling evidence.